Managing Microbes: IMBM And SANBI Collaborate On New Laboratory Information Management System

Data management is one of the core functions of a biobank – and it’s also key to the extent to which the biobank is utilised, especially by external parties. In simple terms: for a biobank to be used effectively, researchers need to know what’s in it (as well as where that’s from, how it was collected, and so on). And that’s especially important when the biobank is one of South Africa’s core microbial biobanks, with over 4000 microbial samples from all over the country.

The Institute for Microbial Biotechnology and Metagenomics (IMBM) is one of the leading research units at the University of the Western Cape (UWC),and is well known nationally and internationally for its research in the fields of microbial biotechnology, bioactive discovery and microbial ecology – work that helps us not only understand what microbes are, but also what they can be useful for.

The IMBM conducts research into microbial biotechnology, bioactive discovery and microbial ecology.

“The genomes from these isolates or metagenomes are largely unexplored, and therefore harbour great potential for the discovery of novel, high-value natural compounds for product development,” explains Dr Anita Burger, Research and Innovation Manager at the IMBM.

As part of this research, the IMBM has established a diverse microbial collection from indigenous and extreme environments, including South African marine and medicinal fynbos.

“To date the IMBM Biobank has been using Excel to manage the entries in the Biobank and the metadata associated with it,” Dr Burger notes. “In my opinion, the key to optimal usage and long-term sustainability of a biobank, is a data management system that is able to capture the different fields of relevant information, and that is easily accessible and user-friendly, allowing users to search the fields of interest.”

The IMBM wanted to format selected fields of information in such a way that it would be searchable by parties who are interested in accessing the collection. This would include the metadata associated with each of the strains such as the origin (i.e. the SA environment that it was collected from), cell and colony morphology, bioactivity data, classification, and whether the genome sequence of the strain is available or not.

For this, the IMBM Biobank needed some expert assistance – so they approached the South African National Bioinformatics Institute (SANBI-UWC) to help develop a fairly simple laboratory information management system that is customised for the metadata fields of the IMBM Biobank database, and that can be used to expand functionality and increase visibility by creating catalogues: Baobab LIMS Lite.

The IMBM Biobank holds microbes from all over South Africa, including bacteria from the coast, medicinal fynbos, and extreme environments like hot springs and salt pans.

Growing With Baobab: A Biobanking Collaboration

SANBI’s Baobab LIMS is an African-led innovation, a laboratory information management system (LIMS) designed by and for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), who, due to financial constraints, are rarely able to implement a LIMS. Since its inception, Baobab LIMS has been used in dozens of African countries, and customised for use in various settings.

But while Baobab LIMS is both free and open source, it’s still not ideal for every situation.

“Baobab LIMS is highly focused on the collection activities of human biorepositories,” Dr Dominique Anderson, PhD, Senior researcher and team lead for Biocollection Informatics at the South African National Bioinformatics Institute (SANBI), explains. “Furthermore, this system has extensive expanded functionality which some users may not need to use, and which can be complicated to navigate.”

In late 2023, the team at SANBI embarked on developing Baobab LIMS Lite, a system designed to deliver core functionality for users in any discipline whilst adhering to international best practices for biobank information systems. And in 2025, the system will be customised for the IMBM, under the leadership of Dr Dominique Anderson from SANBI, in partnership with Dr Anita Burger and Stephanie Lawrence from IMBM.

So what makes Baobab LIMS Lite so…well, so Lite? What makes it so useful in a developing world context?

“Baobab Lite has reduced functionality to make the system more user friendly,” Dr Anderson notes. “While maintaining the core functionality prescribed in best practices, it is also far more streamlined to accommodate diverse users.”

Core functionality includes the ability to configure the system to meet the unique design of the biorepository, including the creation and management of storage units and subsequent sample and sample metadata management, and to track the life-cycle of specimens.

Under an innovation grant, Baobab LIMS Lite will be customised for the microbial biorepository activities being undertaken at the IMBM Biobank, with the goal of providing an informatics solution for this valuable biodiversity collection.

“In the first phase, we introduce the core LIMS prototype, with generalized features, making sure that the core is suitable and user friendly. The second phase, whereby we customize the core for IMBM, is planned for the third quarter of 2025. Finally, we are planning to create a virtual catalogue from data entered into the LIMS, by Q2 of 2026.”

IMBM Biobank Curator Stephanie Lawrence, IMBM Innovation Manager Dr Anita Burger and SANBI-UWC Senior Researcher Dr Dominique Anderson are working on refining the Baobab LIMS system.

Better Biobanking Through Baobab: Why Does It Matter?

“The ability to search the IMBM Biobank for bacterial strains with particular properties, bioactivities or the availability of genome sequence data, etc., will be a major step towards ensuring its sustainability,” Dr Burger notes.

Two major benefits of the proposed system are:

- the system is the first step towards robust informatics-based sample management, with the ability to use permitted data to build digital catalogues; and

- the new system will form the foundation which can be used to expand the functionality in line with user need, allowing for the tool to be more broadly applicable for use by other biodiversity biorepositories.

But the benefits go beyond just one biobank.

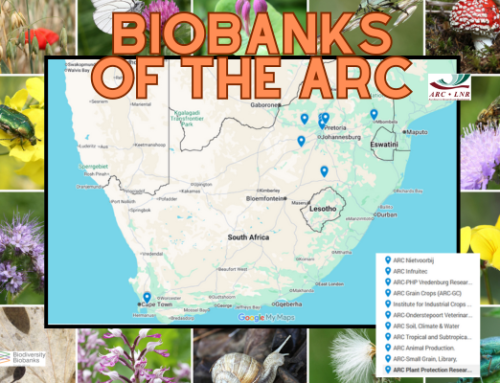

The IMBM Biobank is a core member of the Biodiversity Biobanks South Africa (BBSA), a DSTI-funded research infrastructure project that unites many of South Africa’s biobanks, dealing with everything from sheep to sharks. By partnering with various institutions, the BBSA promotes the value of the biobanks and enhances use of biomaterials for innovative research and development to benefit society.

“Many of South Africa’s biobanks still use Excel for their databases,” Dr Burger notes. “This is not ideal for generating a system which represents the BBSA collections (and in future hopefully other South African collections) and that can be searched by interested parties for the material that they are interested in.”

There are other data and laboratory information systems available – and several of the BBSA biobanks use the open-source Specify Collection Management Platform for the data associated with their specimens. But the proposed system may serve as an alternative more suitable for other South African biobanks.

“The beauty of Baobab Lite is that the core can be customised to suit the specific needs of the user,” Dr Anderson says. “For example, IMBM might wish to capture sample metadata specific to microbial collections, such as bacterial colony morphology, while a botanical collection like the SANBI Wild Plant Seedbank might instead want fields pertaining to GPS coordinates.”

Making material available to interested parties will benefit the sustainability of the respective biobanks, and can help address a variety of biodiversity challenges, and feed into South Africa’s bioeconomy.

“Biodiversity biobanks are crucial in driving foundational knowledge, conservation science, a thriving environment and a sustainable future for all,” says Dr Mudzuli Mavhunga, Acting Lead of the BBSA. “By managing these collections in a structured and transparent manner, we can leverage the genetic diversity resources they house to explore Earth’s diversity and to help us deal with the modern-day global health, food and environmental challenges we are faced with.”

Want to know more about the Institute for Microbial Biotechnology and Metagenomics? Why not visit the IMBM website or watch this video? Or interested in learning more about Baobab LIMS? We’ve got you covered. And while you’re at it, why not learn more about what biobanks are (and aren’t) all about?

What are biodiversity biobanks?

Biodiversity biobanks are repositories of biologically relevant resources, including reproductive tissues such as seeds, eggs and sperm, other tissues including blood, DNA extracts, microbial cultures (active and dormant), and environmental samples containing biological communities….